| Culture : Culture of the Shefings : Shefing Lands | Back to Shefing Culture |

The Lands of the Shefings

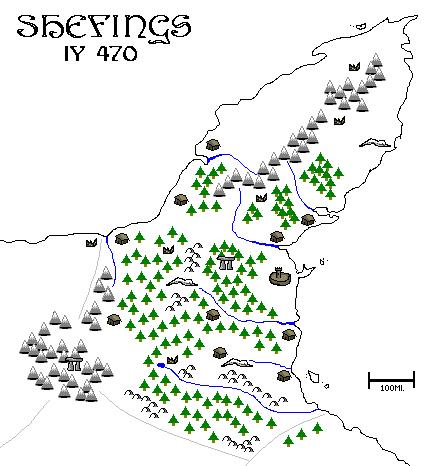

Those who live in Shefings sometimes think of their realm as two lands: one of winter and one of summer, one of tundra and one of taiga, one of darkness and one of light. A true Shefing, it is said, finds beauty in all seasons and all places.

At its northernmost point, Shefings lies about 5 degrees south of Caedes’ arctic circle, or at approximately 60 degrees north latitude. Because of its proximity to the north pole, the land receives about five hours of daylight at winter solstice and 20 hours of daylight at summer solstice.

Shefings generally experiences pleasant summers and frigid winters. Summer temperatures can climb as high as 85 degrees Fahrenheit in the forest, but usually hover in the high 50’s right along the coast. Winter temperatures throughout the domain can stay below zero—and feel even colder due to strong northern winds—for many weeks at a time. Precipitation ranges from 50 to 200 inches annually, falling most heavily in the coastal provinces. Higher amounts are not unusual; Roykenskapa has been known to receive 400 inches of snow during particularly brutal winters.

Visitors to Shefings are continually amazed by the vastness of this untamed, uncivilized land. Its dense pine forests, wide-open expanses of tundra, and miles of ice-choked coastline seem to go on forever.

Shefings is underlain by what some scholars call “discontinuous permafrost.” To the natives, this simply means that the subsoil remains frozen for stretches of two or more years before experiencing a thaw. This condition can affect natural and manmade features in a number of ways (but the Shefings have devised clever means to circumvent these problems): For example, structures built while the ground is frozen may sink or tilt when it eventually thaws, and in warmer months, hundreds of ponds and marshes dot the tundra because the ground is unable to absorb rainwater and melted snow.

The southern provinces of Shefings lie entirely within the thick taiga. The dense timberland of these provinces comprises miles of paper birch, quaking aspen, white spruce, and pine species. The forests throughout the realm produce enough timber to provide Shefings with healthy lumber trade and shipbuilding enterprises without excessive cutting that would damage the environment.

The forest does not end decisively where it meets the tundra. Instead the change is a more gradual thinning of the trees. The heavy spruces and firs give way to scrub trees, smaller and spindlier than their southern neighbors, and create acres of “dwarf forest.”

As the climate grows colder to the north, trees often grow for years on shallow roots above the permafrost; when the thaw comes, the pines sink and tilt. The off-balance, tottering look of such trees earns these regions the nickname “drunken forests.” The dwarf forests eventually give way to shrubbery and laurels, then tundra.

When the folk of Caedes’ southern climates think of tundra, they generally envision flat expanses of unyielding frozen wasteland where ice and snow cover the treeless terrain, and frigid northern winds slice through layers of clothing to bite those who venture out of warm homes. That is tundra in winter. In summer, the tundra comes alive with plant and animal life. Though the subsoil remains frozen, the topsoil thaws and retains large amounts of water, forming hundreds of small marshes and ponds, and enabling the land to support many species of moss, lichen, sedge, and other low-growing vegetation. Because vegetative residue over the centuries has built up a generous layer of peat, and because the roots of existing plants are so shallow, tundra actually forms a soft “carpet” that springs when travelers walk on it. The summer tundra bears one of Shefings’ greatest sources of natural beauty: wildflowers. In late spring and summer, the plains explode in color as millions of wildflowers awaken. The land displays hundreds of varieties including arctic lupine, cotton grass, fireweed, forget-me-nots, marsh marigolds, primroses, and twinflowers. Wild blueberries, cloudberries, crowberries, raspberries, and poisonous baneberries also add to the panorama of color. Highbush cranberries are one of The Mother’s blessings; the shrubs never drop their fruit in autumn, and the frozen berries have been known to save winter travelers from starvation.

Though the northern reaches of Shefings support nomadic clans in the summer, only the intrepid Njorldar clan occupies this area in the winter—and even then the clan retreats south to the tiaga during the most harsh winter months.

Shefings is home to three glaciers. The glaciers are thought by scholars to be remnants of a continental glacier that once covered the region. (Commonfolk harbor suspicions that they are the creations of frost giants.) These giant ice formations are so thick and dense that they actually appear blue. Drifting through the blue ice are visible black streaks, the result of dirt and crushed rock picked up by the glacier. The largest of Shefings’s glaciers is Narikja Glacier, in the southern Hjolgrun hills. It is named for an old legend that claims it was formed by the Lady of Mourning’s tears. This glacier extends about 15 miles and has been retreating for the past 80 years, carving out kettles and leaving moraines in its path. Narikja Glacier feeds the Aald River.

Vika Glacier lies just southeast of the town of Hogunmark. This small glacier has become more active in recent years, advancing at nearly three times its normal rate (now moving approximately three feet per day) toward the sea. It serves as the source of the Bjark river.

No one paid much attention to Northernmost Nevian Glacier until about a year ago, when it reached the Brighteast Ocean. Now Nevian has started calving—in warmer weather, huge chunks of ice break off and fall into the sea, where they become icebergs. Those who circumnavigate the nation of Stahlings fear the trip may eventually become too treacherous to navigate.

As glacier-fed rivers, the Aald and the Bjark carry large amounts of glacial silt. During movement, the glaciers grind rocks, trees, and earth into a powder as fine as flour which then enters the river when the ice melts. The silt is so fine that it doesn’t settle in the riverbed but remains suspended in the water, giving the river a milky-brown color. Little fishing is done on the Bjark River; because the silt is so blinding, salmon in particular avoid the waterway. A peculiar strain of eyeless fish is known to inhabit the Bjark; on the rare occasions that such a fish is caught, superstitious locals believe this to portend ill luck for the unfortunate fishermen. When the silty water meets the clear water of the sea, the two swirl and roll and billow until they finally blend. The sylvan elves call this phenomenon abheath (ah-VEY-ith), meaning “wedding of the waters.” Eventually the silt settles on the ocean floor.

The domain’s other primary rivers are the Ojyron and the Ynavik. These rivers provide most of Shefings’ salmon harvest each year, and is heavily fished by the Halskorrik and Rolulf clans during spawning season, respectively. The Ojyron river is home to king, red, and chum salmon, while the Ynavik which flows from lake Umberlupus also supports the rare silver salmon. The Hjarring River, which serves as the border to Asclings along with the Great Berg Mountains, is used mainly for transportation. The two Northernmost rivers, the Hlavik and the Godsmir are used to collect trade goods transported south from the tundra.

The domain’s coast stretches for miles and is pocketed with many capes and harbors which lends to the nation’s seafaring capability. Those not locked by ice in winter are able to stay busy year-round launching “exploration vessels” and participating in trade. Ports farther north than the tiaga line manage to stay open by employing icebreaker vessels to keep harbors clear.

Shefings shares borders with many hostile forces. Sometimes, however, the kingdom’s most threatening neighbor is the sea. Mariners sailing from one side of the nation to the other must navigate the cape of Roykenskapa which marks the boundary between the Miere Dunord with the Brighteast Ocean. The iceberg-choked, stormy waters have caused the demise of many of the finest Shefings vessels. In winter, the solid sheets of ice are so thick and stretch so far out to sea that one can walk from the mainland to Selkie Island. Nomadic clans that occupy northern coastal provinces in summer months find all manner of interesting and valuable items washed up on shore.

Though humans have ruled Shefings for centuries, the land remains nearly as wild and untamed as it ever was. Those who leave the safety of settlements could find danger lurking around any tree or riverbend.

Mammals common to northern climates freely wander Shefings’s forests and tundra. Like the domain’s nomadic clans, these creatures generally retreat to the taiga forest in winter and venture into the tundra as the weather warms. Moose, elk, caribou, brown bears, and lynx are frequently seen; wolves, including winter wolves, are quite common and are even known to roam the streets of small villages at night. (In Shefings, the phrase “the wolf at the door” is not merely a metaphor.) Smaller mammals such as beavers, foxes, muskrats, minks, squirrels, and snowshoe hares appear throughout the domain. Hunters prize all of these animals for their furs. Fortunately, the realm’s most dangerous creatures inhabit only particular areas of the Shefings. White puddings offer a deadly surprise for travelers crossing the tundra in winter. Occasionally, remorhaz (polar worms) have also been spotted on the tundra plains. Roykenskapa, Shefings’s northern-most point, is said to be the home of storm and/or frost giants depending upon which terrified witness or boastful adventurer one asks. In the domain’s treatcherous Eldcragg mountains which runs through the center of the forbidding tundra, frost giants have built a kingdom of their own ruled by a charasmatic frost giant lord. Ice trolls live near Nevian Glacier and at the headwaters of the Hlavik River. Primitive bugbears and ogres patrol large, uninhabited tracts of forest land in the tiaga, and Skalds carry tales of nymphs appearing now and then in the thickest parts of the taiga forest.

Many varieties of birds and waterfowl grace the skies and coastlines of Shefings. Some of the more common species include terns, eagles, falcons, loons, geese, ducks, wagtails, and, on the tundra, ptarmigan. Sea otters are a common sight along the coast, as are seals, walrus, whales, and narwhals. Selkies are said to populate the island that bears their name, though their existence has never been proven and no one actually lives on the island to bear witness. The cape of Roykenskapa is home to a species of fierce, aquatic, serpentlike creatures known as Unnskrajir. These sea monsters can pose as much danger to sailors as that water’s storms and ice-bergs.

Shefings is dotted with ruins and fallen temples to prior gods and regimes that have long fallen. In addition to the druidic Gret Stones found in the Great Berg mountains, the pagan shrine of Council Grove sits deep within the forest west of the city of Veikanger. Council Grove is a small stand of trees historically important to Stahlings. Here, the Three great kings of yore Harr, Ing, and Gorm met in secrecy to detail their initial attacks on the serpent-folk. Later, Wjulf was proven to be of Shef Greenshield’s line and was named the domain’s first king.

Thought to be a place of ancient pagan magic, the grove never suffers the ravages that winter inflicts on the surrounding terrain. Though snow falls and temperatures drop, individuals standing within the grove remain safe from the fury of storms and the predatorial instincts of starving wolves. The jarls once convened annually in Council Grove, but have long since moved their meetings to within Veikanger’s walls. As most Stahls, the jarls felt uncomfortable gathering in a place touched by magic; that distrust lingers to this day.